Buddhist Women on a Path of Spiritual Awakening

Giving to What We Love

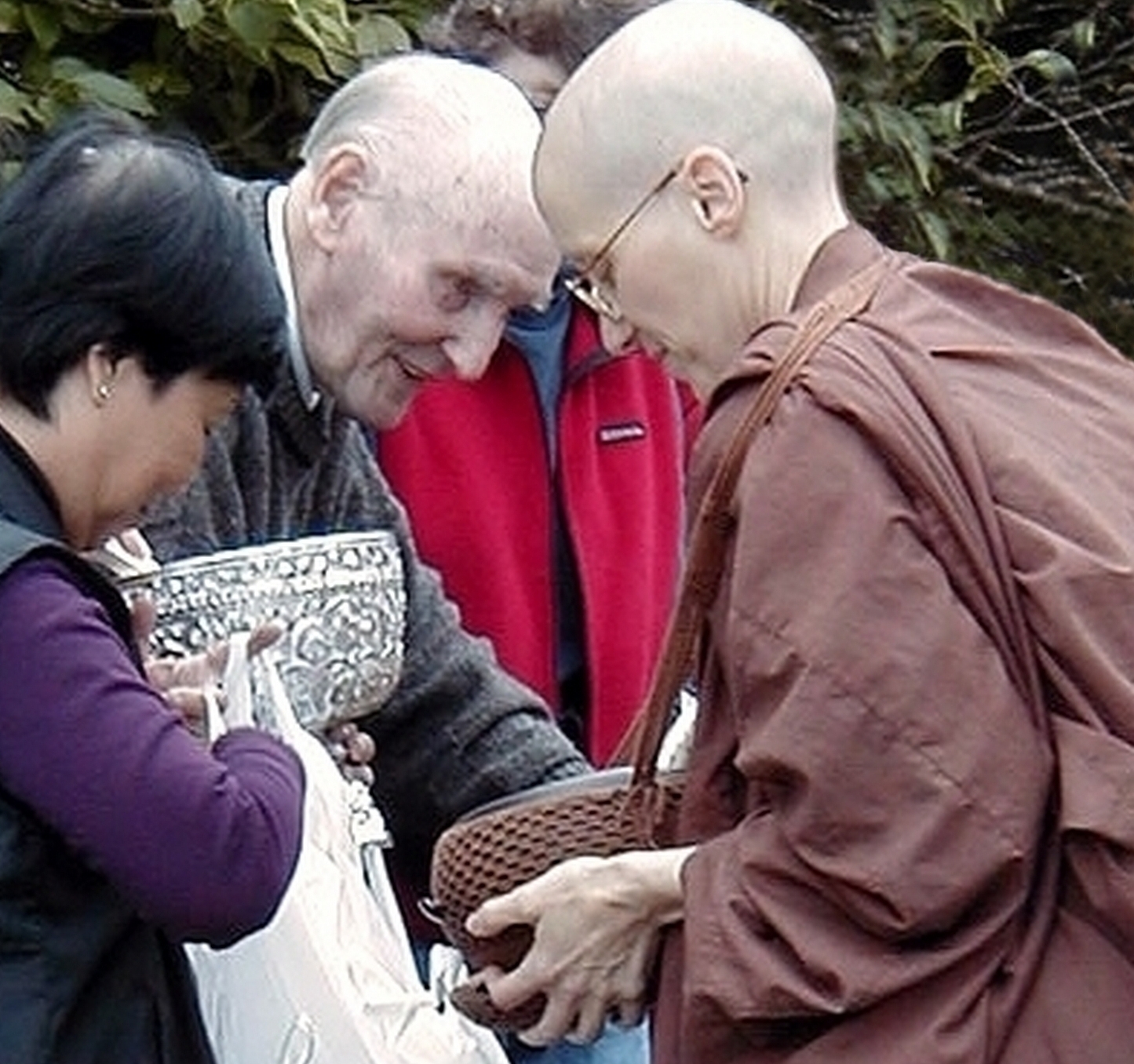

One morning, as I stood for alms in an outdoor market, an elderly man supporting himself with a walker shuffled awkwardly towards me. His daughter held him on one side with her arm. As soon as he saw my robe and bowl, and the shaven head, he let her go and, with palms pressed together, he made anjali, respectfully bowing his head and incanting the formulaic ‘Sadhu, Sadhu, Sadhu’.

Then, in wholehearted abandon, he began to pick fruit from a nearby vendor’s stall. At first he placed two apples into my alms bowl. Spotting a fancier variety, he set about selecting the choicest he could find. As he reached for the grapes, the shopkeeper intervened and motioned to him to hand over the fruit for her to wrap. But when she saw the cause of his excitement, she softened. For he was swept up in the devotion of giving and could not offer enough.

So effusive was his joy that he appeared to have forgotten his disability, his daughter, the fruit vendor and the protocol of the market. Beyond apples and grapes, the old man harvested the finest imported fruit with the urgency of one feeding a long lost friend – as if in that brief encounter he would offer all the generosity of his lifetime.

That kind of selfless generosity informs the power of my faith and renunciation. It acknowledges the sacrifice I make for what we both know to be true. And it nourishes my body and my heart. In the humbling that comes from walking life’s byways, powerless and content with little, I learn to trust giving myself to the unknown. And mysteriously, kindness provides for me.

Sometimes it is abundant, sometimes not, sometimes pleasant, at other times not. This is a universal predicament. None of us know what will come next and how we will respond – especially in this age of outrageous and unrepentant global violence. Though we may, for the most part, live with calm and confidence, until the mind is trained, sometimes all it takes is one grenade of a bad mood or internal ill-wind to blow before we are inundated by negative feelings.

As a mendicant, my happiness hinges upon the way I am able to bear not just physical rigors, but all the austerities of life. Whether I am praised or criticized, comfortable or challenged, calm or in despair, instead of following the bleak and destructive habits of the mind, I try to remember to be empty like my bowl, accepting whatever tightness of breath or furrowing of the heart may arise. And I use the mantra that everything is there to teach me. So as long as I am able to invoke gratitude for what is, I taste the unexpected benefit of being a beggar in the face of the present moment.

What this means is, whether I live in community or alone, I have to guard the mind constantly. We have all seen how easy it is to get rankled by an unforgiving remark or interaction that can swiftly erupt in reactivity – feeling good enough, not good enough, worthy, unworthy, proud or humiliated; or being disabled by a sense of vulnerability that loses mindfulness, denounces the situation, and broods over what’s lost or could have been.

A weak mind runs to thoughts of blame – outward or inward – instead of to thoughts of blessing. Whether from the crushing feeling of social pressure or the thrashing of the internal critic, the mind habitually retreats from pain, yearning for safety. And that safety is to be found nowhere else but in the silence of being with the way things are.

Again and again, I call on patient acceptance, unruffled resolve and perseverance as my allies in these seemingly irredeemable moments. Staying centered, aware, and clear, a benevolent wind wafts into my sail and calms the inner space enough to navigate my way back to serene and joyful presence. And the stamina to sustain that well-being develops by diligently letting go and not clinging to what is unwholesome and obstructs mental clarity, peace and wisdom.

Ultimately, the trust with which I give myself to the unknown moment comes from a heart that is open and willing to surrender. It is a generosity of spirit that enables me to move out of complacency and take risks. This quality of giving must renounce any trace of selfishness. It can be neither smug nor self-congratulatory. It is asks nothing in return, like the elderly man in the market who so caringly fed me, a complete stranger. But he recognized the beggar, dressed in the robe of the Buddha.

Such unconditional generosity springs from and feeds a transcendent joy. For in giving to what we love and respect, we nourish the goodness in ourselves. And it is mutual. I become – for the giver, as well as for myself – the fourth of the Heavenly Messengers, a renunciant.

My aging body and the illnesses of recent years serve to remind me of the first three of these messengers – old age, sickness and death. And in the frailty of his advanced years, my old benefactor also acts as their herald – more potent for the way he overcame even physical dysfunction by the ardour of his faith.

Devoted to this work of emptying and opening the heart, the fruits we taste, like the joy of offering and receiving, are greater than those of the earth. They are indeed heavenly – beyond pain, beyond death.

© Ayyā Medhānandī

Posted in a 2006 series of blogs that appear under ‘Penang’s’ blog on the ‘Teachings’ page.