It’s December again. The malls are manic with shoppers thronging to eateries, shows, and sales of every conceivable electronic gadget. Strolling in air-conditioned euphoria under mammoth snowflakes that hang precariously from on high, you can catch sight of Santa Claus sailing a Norse longship with a polystyrene chicken and a gingerbread man as First Mate. I prefer a quiet walk beside the sea under casuarinas and coconut palms laced with jewels of light.

Few here know the story of Christmas. Still, most will join the frenzied merriment of buying and receiving presents. The practice of generosity is supposed to turn us away from self-cherishing. How can it when we are raised on a diet of getting what we want from the tooth fairy or our parents for every good grade, birthday, or holiday we celebrate? As long as we are fed by a culture of materialism, what can be the true marrow of our giving?

There are many reasons we give: out of love, sympathy, gratitude, wanting to flatter, impress, appease, pamper, or reciprocate. We also give because it is expected of us, we hope to exact a favour, or want recognition. And there are as many possible outcomes. Whatever our impulse, the results can be destructive – particularly when we endeavour to buy love from each other; or with our own children, use gifts to compete for their affection.

Being honest about our intentions – no matter how self-serving – can steer what, how, to whom, and when we give. A gesture of friendship may be more meaningful than flamboyant expense for the wrong thing. When would you offer it? In public or invisibly? Is it for someone you respect or do you feel obliged? Would you ignore an addict begging on the street? What if it’s your own child?

As a mendicant not handling money, I am caught in the paradox of being unable to buy presents yet wanting to give them. In a monastic calendar packed with ordinations, festivals, retreats, and rituals honouring our teachers, opportunities for exchanging gifts abound. We become adept not only at recycling what we have received but also making something out of nothing.

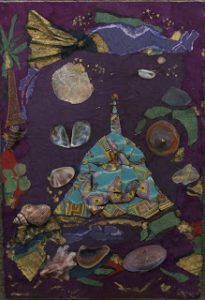

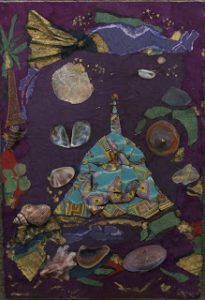

The cards I create from scraps of fabric, broken pots, shards of glass, shells, wood, feathers, stones, sand, skeleton leaves and dried flower petals become poems and prayers of well-wishing. As I give them away, I have to ask, “Why am I doing this?” What I discover about myself is not always uplifting – sometimes an eagerness tainted by expectation, at other times resistance when I have been coerced into giving.

During one of our annual kathina* events, well into the night I painstakingly prepared a special card for an elder with some of my best collectibles. After discreetly propping the finished product against her door, I came away well-pleased, certain that she would be effusive. The next day, her lukewarm response left me understandably crestfallen, and confirmed what I already knew. I’d been fishing for approval – hardly unconditional dāna*.

Despite its obvious spiritual value and the joys associated with it, sometimes giving comes hard. A friend travelling overseas asked if I wanted him to bring a gift on my behalf to a mutual acquaintance – someone I had grown to mistrust over the years. My hesitation was palpable. “Don’t you want to send a card or small gift?” he prodded innocently.

Embarrassed, I felt compelled to produce an offering, at least as camouflage for my faux pas if not out of genuine friendship. Surprisingly, I found myself not only making a card and wrapping it with care but also trying to think positively of someone I had long shunned. By the time the package was ready, it had already become a gift – to me.

Generosity contains the whole path – from precepts to liberating consciousness. But to mature and develop it well, we may have to confront charred memories and perceived injustices that stall and weaken our ability to be magnanimous. Ferreting out our intentions – whatever they are – enables us to see through, and try to forgive the mind’s covert games or prolonged tantrums. We can then dislodge selfish and caustic attitudes, or entrenched feelings that divide us from others as well as from the riches of our own heart.

As long as we determine not to compromise what is true, we can trust our own goodness. Then, when we do give, it is from an unsullied place that extends well beyond self-concern and self-congratulation. Guided by wisdom, at least we try to act from loving-kindness.

One afternoon, reminiscing about times of personal suffering, a brother monk recalled his worst experience of pain following an operation to remove a kidney he had donated anonymously. In time, he met the recipient, a young village mother. He quietly recounted the joy of restoring her life and staying in touch over the years as she raised her children.

Perfect giving is truly selfless and compassionate – and is its own reward. We may not be required to be so heroic as donating a kidney but we all can practise kindness in small, ordinary, hidden ways with no thought of return: help carry a package, take in a neighbour’s laundry when it rains, or buy a coffee for someone having a bad day. It need not cost much. Just letting that person know that you care or being there for them is a joy – perfect in itself – and a gift for all seasons.

*dāna: offerings to the Sangha

*kathina: robe-offering ceremony at the end of the Rains Retreat

© Ayyā Medhānandī

This a post from Ayyā Medhānandī’s blog written while based in Penang. She draws on her experiences in a monastic community in England as a solitary nun in a coastal hamlet of New Zealand and as an urban nun perched in a ‘sky temple’ overlooking the Malacca Straits. Other posts from this blog can be found under “Penang’s Blog” topic category.