Buddhist Women on a Path of Spiritual Awakening

Jingle Belanja

During my kappiya’s long search for suitable accommodation, a handful of owners refused even to show their rental properties once they were informed she would be housing a Buddhist nun for several months of the year. One building manager declared that renting to Sangha* would not be ‘fair’, whatever that meant – and he was Buddhist!

The others conveyed their wishes through estate agents. Such overt discrimination is surprising for Malaysia, a predominantly Muslim land, blessed with a rich tapestry of races and religions. In this exotic melting pot, the main Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu festivals are also national holidays.

Christmas Day is a good example. While locals of other faiths may not know what it’s all about, they happily join the celebrations. Traffic swells the streets as families venture out to air-conditioned malls, parks, and beaches to spend time together. By early morning, food stalls of every flavour are magnets for hungry customers.

I am invited to share a meal of typical Malay cooking with my devotee’s family. Decanting from the bus into the mayhem of vehicles, we meander towards the street stands where a colourful display of mild and hot curries, sambals, and a smaller selection of vegetable dishes have already attracted a crowd.

Inside the restaurant, we save a table large enough for us all to sit together. Mindful of completing my meal by midday, it’s already time to join the punters milling around the trays of food. In one corner, we discover the giant cauldron of boiled rice. This is the starting point.

I stand quietly holding my bowl. A gruff middle-aged Malay man in his long apron is busy dividing a stuffed omelette. He brusquely orders me to wait as if to assert that only he can serve the rice.

Patience always redeems such moments. In the commotion of plates being heaped full, I wait. A second man in charge, burly but with a beaming face, approaches the pot and lifts its lid. “Fresh rice is ready,” he confides pleasantly in perfect English.

Encouraged, I watch him supervise two kitchen helpers hoist the new pot into place. Once it is installed, he reaches to fill a plate for me. My kappiya protectively intervenes to explain how the offering is done. Smiling, he generously scoops the steamy rice into my bowl.

Next, we tussle to reach the vegetables where she plies me with spicy petai, beansprouts and a melange of greens, then return to the friendly owner where she can pay. Peering at the contents of my bowl, he chats exuberantly with her in Malay – to be certain that the selections are acceptable – and ends with the word ‘belanja’. This is to be his dana* – a treat.

In the frenzy of collecting our food, one simple gesture of kindness dispelled all trace of frustration. Nor did the charm escape me that, as a Western Buddhist nun, here I was receiving dana spontaneously offered by a Malay Muslim patron on Christmas Day in a Chinese Taoist eatery – enough to restore my trust in human nature.

After we settled ourselves indoors, I made dedications and softly chanted the sharing of blessings. Nearby, the proprietor of the building sat nodding approvingly as she observed our ritual. A few staff and onlookers stood by in curious appreciation.

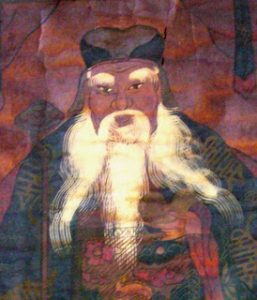

Through a kitchen door, the startling face of a Taoist god of prosperity presided over a shrine of burning incense and half-melted candles, his copious white eyebrows and beard as time-worn as the smoky walls and bare crimson light bulb suspended from the ceiling. Under the surreal gaze of this god-figure, a cacophony of street sounds, kitchen clatter, conversations, and radio music percolated vibrantly through the hall.

Through a kitchen door, the startling face of a Taoist god of prosperity presided over a shrine of burning incense and half-melted candles, his copious white eyebrows and beard as time-worn as the smoky walls and bare crimson light bulb suspended from the ceiling. Under the surreal gaze of this god-figure, a cacophony of street sounds, kitchen clatter, conversations, and radio music percolated vibrantly through the hall.

I feel at home here – not least for this unpretentious fusion of diverse peoples enjoying each others’ foods and festivals – but especially for the simple acts of kindness that defy religious and cultural boundaries and differences. Just as calling someone overweight ‘Fatty’ is not considered an insult here, being refused tenancy by a few landlords may simply echo that same honesty about one’s feelings.

In a Western setting, such language might sound politically incorrect if not impolite. Here, it seemed more likely an attempt to protect the sanctity of their own tradition rather than discriminate against my way of practice. Like the requests for prayers I receive from friends of every faith, today’s Yuletide belanja manifests the power of respect and kindness to repel the bigotry and hatred in this world.

But it must begin at a personal level, human to human, eye to eye, smile to smile. From such seed true peace is born.

*Sangha: Buddhist monks and nuns

*dana: meal offering

© Ayyā Medhānandī

This a post from Ayyā Medhānandī’s blog written while based in Penang. She draws on her experiences in a monastic community in England as a solitary nun in a coastal hamlet of New Zealand and as an urban nun perched in a ‘sky temple’ overlooking the Malacca Straits. Other posts from this blog can be found under “Penang’s Blog” topic category.